Longevity for pets: why should we care

Systemic, physical and functional changes related to aging in dogs, cats and horses and how good of a model are each of them for aging in people

Mooncake, the adorable fluffy brown angel 🐈 has been part of my life since I adopted him about three years ago. Freyja, the tiny cute black devil 🐈⬛ arrived one year after that. They are still young so I haven't thought much about their longevity. That's until the beginning of March 2023 when Loyal announced that they received protocol concurrence; which means the FDA agrees with the clinical trial they proposed. Their goal is to demonstrate that a longevity drug extends healthy lifespan for dogs: extend lifespan but also to ensure a higher quality of life during those additional years. The results will be enough to support bringing the drug to market.

This is huge for the longevity space because it will be the first time a company will do a clinical trial for lifespan and healthspan. And is huge for dogs for obvious reasons. But is this huge for people too? And what about cats? And horses?

I went down the rabbit hole to learn more about the biology of aging and the science of longevity for our most beloved companions. And I want to share it with you. Initially I was just going to write one post but more than 100 papers later I realised I have to break it down into a series.

The underlying mechanisms of aging are so complex that most of what we know about them comes from studies in simpler models: yeast, worms, flies and mice. And it's not clear how much of what we already know can be translated to people. Dogs, cats, and horses, like us, live way longer, are genetically diverse, don't spend their entire life in a lab, and receive specific care when they get ill. This is important because having more in common with us could make them better models for aging in people.

Understanding how our companion animals age not only benefits their health and well-being but may also provide valuable insights into how we age. Many of the same mechanisms that underlie aging in animals are also at play in people, so studying these processes in pets could ultimately lead to therapies for slowing down and even reverting aging in people.

Mooncake 🐈 and Freyja 🐈⬛ will experience many of those molecular and cellular changes as they age. None beneficial or desirable. We’ll go through all of them in the next posts: nutrient sensing, metabolism, inflammation, immune system, etc. But in this first one I just want to take a step back and discuss some physical and functional changes related to aging in dogs, cats and horses. And how those changes are similar or different with the ones that happen to us.

Lifespan

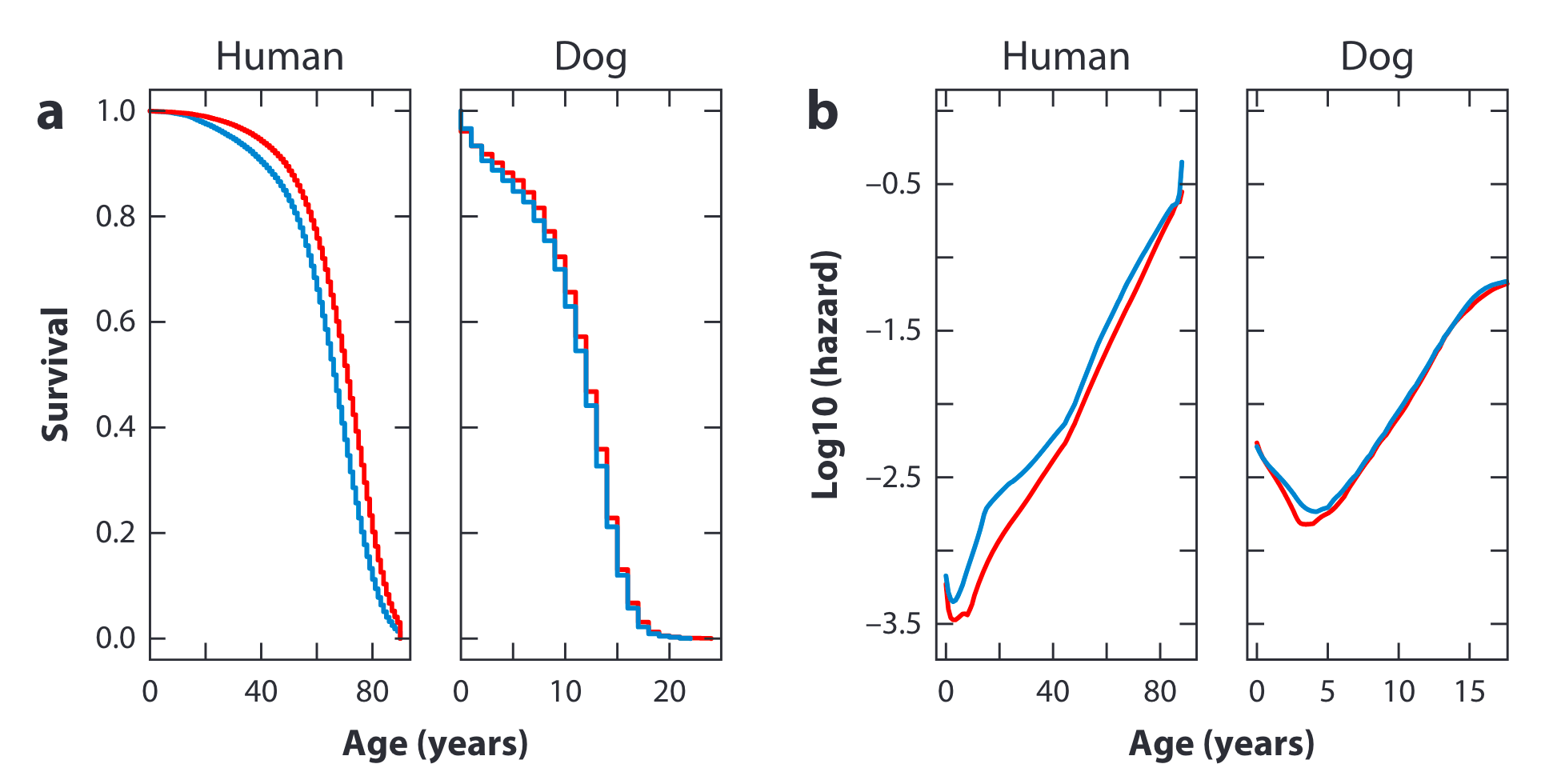

Dogs age approximately six to seven times faster than people, although not always at the same rate. Especially when dogs are young, they age rapidly compared to people [1]. Cats usually live longer than dogs. They are considered mature at 7-10 years, senior at 11-14 years, and geriatric at 15+ years.[2] Horses are the ones who live the longest. They are considered mature at 5 years and geriatric at around 15 years when the first signs of aging start to be noticeable.[3]

Among species, larger animals tend to live longer than smaller ones, however, the opposite is usually true between individuals of the same species. Smaller dogs tend to live significantly longer than larger dogs across all breeds.[4] Large dogs (above 50 kg) like Great Danes and Bouviers generally live for 6-8 years, while small dogs (below 10 kg) like Chihuahuas and Toy Poodles can reach 14-16 years.[5]

Cats and horses are not as phenotypically diverse as dogs. Especially not in their size. But lifespan depends on many factors: breed, exposure to injuries and disease, environment, stress, and nutrition. Neutered cats and dogs live longer and experience reduced risks of asthma, gingivitis, hyperactivity, and other issues.

As a rule of thumb, crossbred cats like Mooncake 🐈 and Freyja 🐈⬛ typically enjoy greater longevity than purebred cats, living up to 14 years compared to 12.5 years for purebreds. Jackpot! But breeds like Birman, Burmese, Siamese, and Persian cats have similar or longer lifespans than crossbreeds. With proper care some cats can live well into their late 10s and even early 20s. [6] This highlights the complex interplay between genetics and environmental factors in determining an individual's lifespan and emphasizes the importance of providing optimal care to Mooncake and Freyja as they age.

Small and primitive horses 🐎 live much longer than large ones. And compared to cats and dogs, they spend much more time in the geriatric phase. Their average life expectancy is 19 years but many horses live past their 30s and some even past their 40s.[7]

All this matters a lot because we can can do studies with cats, dogs and horses and really get answers about the effect on lifespan, life expectancy and longevity in a matter of years. If we did the same studies with people, it would take decades.

Cognition and behaviour

Most companion animals experience behavioral changes as they age. And they are not always a direct result of an underlying or concurrent disease, such as canine, feline, or equine cognitive dysfunction (in the next posts I’ll go deeper into this).

Initial cognitive impairments in dogs 🐕 often develop around middle age (6–7 years), which means many of them may experience some degree of cognitive decline for about half of their lives. Response to commands, decision-making, problem-solving, and learning from past experiences are usually affected. However, some learning aspects, like acquiring new habits and recognizing simple visual patterns, remain relatively unaffected. Older dogs are less interested in playing and walks. This could be a reflection of physical decline, but could also indicate apathy or a reduction in a dog’s awareness of its surroundings.[8]

Dogs are very good evidence that physical activity really is protective against cognitive decline later in life. Regular mental stimulation has been linked to better attention and mental function in older dogs, and may help protect against cognitive decline. This parallel between us and our companion animals shows how important it is to maintain an active mind and engage in mental exercises as we age.

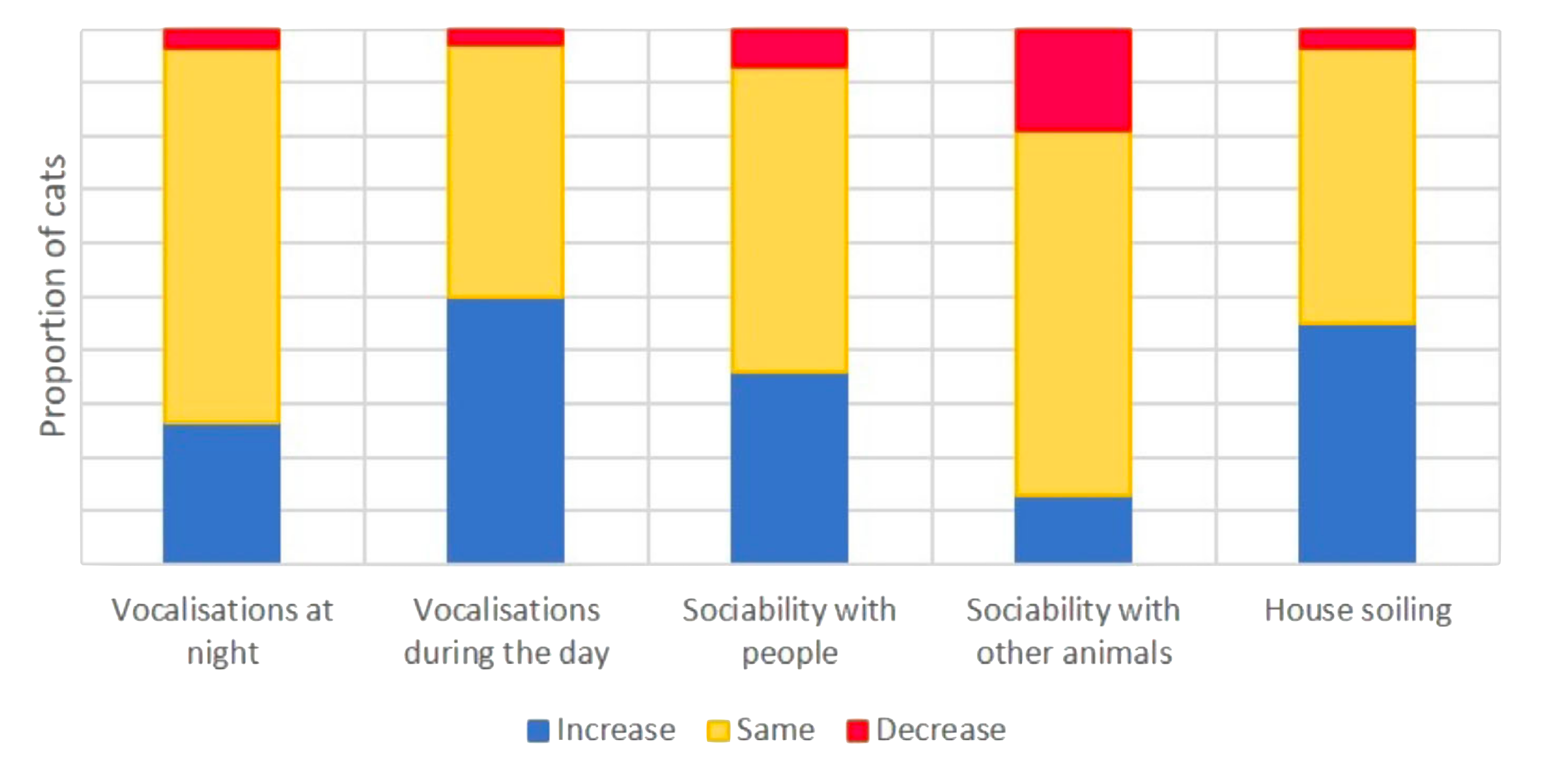

As Mooncake 🐈 and Freyja 🐈⬛ get older, they will undergo changes in cognitive abilities and behavior like altered sleep patterns, vocalizations, stress tolerance, and interactions with family members and other pets. Some middle-aged cats often show positive behavior changes, like increased affection and seeking more attention.[9]

Younger horses 🐎 are generally more reactive and exploratory, while older horses are less responsive and have physiological changes, such as a reduced ability to manage their emotional responses to stress. [10] Horses become more confident, or "bold," as they age, meaning they are less fearful and more willing to confront challenges.[11]

I’m concerned that these changes in behaviour may contribute to the kind of negative feelings parents can have towards older companions. And I can’t stop but wonder how much better it would be if we were able to delay and slow down the aging process.

Body composition, muscle, bones and joints

Like us, companion animals experience age-related changes in body composition, muscle mass, and bone density, which can affect their overall health and quality of life. By studying these changes in them, we could understand the underlying causes of sarcopenia, osteopenia, and other age-related conditions in people, potentially leading to improved prevention and treatment strategies.

In dogs and horses[12], total body fat mass tends to increase with age, along with a shift from subcutaneous to visceral fat. Cats also experience an increase in fat mass as they age, up to around 11 to 12 years. After this age, both fat and lean body mass decline, with a greater decline in fat mass, leading to a generalized underweight condition, rather than sarcopenic obesity. In the next posts I’ll go deeper into how these changes often lead to metabolic dysfunctions, like insulin resistance and increased inflammation. [13]

Like us, dogs and cats both show signs sarcopenia (age-related muscle loss) as well as decreased muscle strength, decreased agility and flexibility. Horses on the other hand, even if they their motor functions decline, it’s not clear that they lose muscle mass to the same extent as people, dogs, and cats.[14]

One common age-related condition shared by people, dogs, cats and horses is degenerative joint disease (DJD), also known as osteoarthritis (OA). Is a condition where the cartilage in the joints breaks down over time, causing pain and stiffness. In horses, OA is particularly prevalent, with more than 50% of horses older than 15 years and up to 80-90% of horses over 30 affected by it.[15] Cats can even experience DJD at a young age, but it may go unnoticed because it often doesn't cause pain or visible signs.

Unlike us, companion animals do not develop clinical osteoporosis. But similar to us, they do develop age-related osteopenia, or reduced bone density.[16][17]

One of the most common orthopedic problems in older horses is laminitis: it affects the hoof and the bones and joints within the foot. It is a painful and debilitating condition that can lead to lameness. Which is a major cause of mortality in geriatric horses and sadly the most common reason for euthanasia. In the next post I’ll go deeper into the primary hypotheses explaining the origin and development of acute laminitis like inflammation, extracellular matrix degradation, metabolic abnormalities and impaired blood vessel function.[18]

The heart

Heart disease is the number one causes of death for people. Period. Companion animals don’t develop atherosclerosis but they do develop some heart disorders as they age. Studying age-related heart disorders in companion animals can teach us about the development and progression of similar conditions in people, potentially leading to new treatment options to improve cardiovascular health for everyone.

The most common cardiac disease in cats over 6 years of age is hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), where the heart muscle becomes abnormally thick. Another one is fibrosis of the intima, a thickening of the inner layer of blood vessels.

Some older dogs and horses develop left-sided cardiac valvular insufficiencies, a condition where the heart valves do not close properly, leading to inefficient blood flow.

Symptoms like cardiac murmurs, arrhythmias (irregular heartbeats), and gallop rhythms (extra heart sounds) are common in most geriatric cats, dogs and horses.[19] But these symptoms may not always indicate severe heart problems. Regular check-ups are crucial for early detection and intervention, ensuring the cardiovascular health of our beloved pets as they age.

Just as people are encouraged to adopt heart-healthy lifestyle habits, it's essential that we also consider our companions’ needs for regular exercise, a balanced diet, and routine veterinary checkups.

Renal, respiratory and endocrine systems

We know very little about age-related changes in renal, respiratory and endocrine systems of companion animals.

Older cats become more prone to chronic kidney disease (CKD), a long-term condition where the kidneys gradually lose their ability to function properly. Additionally, in older cats with CKD, a condition called tubulointerstitial fibrosis, which scars kidney tissue, is most common.

Both CKD and degenerative joint disease have been linked to impaired immune and inflammatory processes. Inflammation and fibrosis in cats over nine years old might be part of a slow, progressing inflammatory process leading to kidney scarring. So in the next posts I’ll go deeper into the molecular and cellular mechanisms of aging that are related to the dysfunction of the immune system and inflammation.

In people, aging affects the flexibility of the lungs, the strength of respiratory muscles, and the ability of the chest wall to expand and contract. Older cats show signs of lung tissue changes and it seems that the responsiveness of the airways decreases in older cats. Respiratory conditions like recurrent airway obstruction (RAO), which is a chronic lung disease causing inflammation and difficulty in breathing, are more common in older horses.[20]

In older horses, pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction (PPID), a hormonal disorder affecting the pituitary gland in the endocrine system, is the most common issue. Over half of the horses in one study showed abnormal shedding of their coats, which is referred to as moulting patterns. However, only a few horses were diagnosed with or suspected by their parents to have PPID. This suggests that parents might misinterpret PPID clinical signs as normal aging and avoid veterinary intervention. The risk of developing PPID increases with age and can be associated with an increased risk of again, chronic laminitis, which is found in many horses with PPID.

Takeaways

Similar to people, as companion animals age, their risk of being diagnosed with various age-related diseases and dying from them increases. So studying longevity through them is essential for multiple reasons. First, it helps us improve their health and quality of life as they age. Second, with their diverse genetic backgrounds and lifestyles, they can be good models for understanding aging in people. Much more than laboratory animals.

If you want to go deeper into this topic, below you can check some papers that helped me write this post.

Quantitative Translation of Dog-to-Human Aging by Conserved Remodeling of the DNA Methylome ↩︎

The Aging Phenomenon of Horses With Reference to Human–Horse Relations ↩︎

Genetic Pathways of Aging and Their Relevance in the Dog as a Natural Model of Human Aging ↩︎

Longevity and mortality of cats attending primary care veterinary practices in England ↩︎

Demographics, Management, Preventive Health Care and Disease in Aged Horses ↩︎

Growing old gracefully. Behavioral changes associated with “successful aging” in the dog ↩︎

Aging in Cats: Owner Observations and Clinical Finding in 206 Mature Cats at Enrolment to the Cat Prospective Aging and Welfare Study ↩︎

Effect of aging on behavioural and physiological responses to a stressful stimulus in horses ↩︎

Age-Related Changes in the Behaviour of Domestic Horses as Reported by Owners ↩︎

Effect of body condition, body weight and adiposity on inflammatory cytokine responses in old horses ↩︎

Effects of advanced age on whole-body protein synthesis and skeletal muscle mechanistic target of rapamycin signaling in horses ↩︎

Musculoskeletal Disease in Aged Horses and Its Management ↩︎

Comparative veterinary geroscience: mechanism of molecular, cellular, and tissue aging in humans, laboratory animal models, and companion dogs and cats ↩︎

Effect of age on bone mineral density and microarchitecture in the radius and tibia of horses: An Xtreme computed tomographic study ↩︎

Muscle Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Horses Affected by Acute Laminitis ↩︎

A survey of health care and disease in geriatric horses aged 30 years or older ↩︎

Estimates of longevity and causes of culling and death in Swedish warmblood and coldblood horses ↩︎